essays

Here too are cemeteries, fame and snow

We have a compelling need to lend form to the universe without destroying its mystery. And so we sculpt its various movements into equations, corsetted by such absurd immutabilities as the speed of light. We raise our telescopes to the skies, and there we find labyrinths rather than fields of stars.

We wish to twist it all into a ball and let it stream like original light from the palms of our hands, but also to be stilled by the rhythms that are reflected back to us. We insist that it is infinite, yet also bounded, just as ourselves.

We wish to venture out into the universe, not just gingerly, but in the hope of transformation. We conceive of objects such as stargates which can plunge us into unimaginable landscapes but ultimately only draw us back in into the territory of our own memories.

We live within a constant current of terror, a permanent awareness of its ability to annihilate us at one stroke, and yet we exult in the poetic possibilties of this eventuality. We relish how it diminishes us, the easy humility that we are filled with simply by lifting our eyes to the night skies.

At one time, we believed ourselves to be at the centre of the universe. Aristotle created a cosmological model out of the complex turnings of fifty five spheres, but it did not explain why planets sometimes seemed to change speed or indeed move backwards. Ptolemy created more circles within circles to accommodate these irregularities. Then, about five hundred years ago, Copernicus put the sun in the centre of the universe; there were others who had done so before him but their ideas had died with them. But that was only the beginning of our insignificance, for soon the sun was to become just another star, and the entire solar system an infinitesimal smear within whirling galaxies. Today, we may talk of of ourselves as mere bubbles within spacetime foam, but we are no less content to be so than the nucleus of it all. Perhaps, it was too large a responsibility for our human shoulders to bear.

At first we could only see what was visible to us by the naked eye (why do we call it the naked eye when it the one part of our body we cannot really clothe?) but then we began to make ever more powerful telescopes to probe its secrets. Here is an image for you: in the dark, damp cellar of an elegant Georgian townhouse in the city of Bath in England is a man grinding a mirror on a mould of horse dung - he cannot interrupt his work but he is hungry, so his sister is putting pieces of food into his mouth, and after he has eaten she will read to him from Don Quixote while he carries on with his work. This man is William Herschel and he is determined to build a twenty foot reflecting telescope so that he can map the universe; the sister who is feeding him is Caroline Herschel who will become one of the world’s first woman astromers and discover seven comets. But at this time, they are both musicians, earning a living in the fashionable spa town of Bath where William has a well-paid job as organist to the Octagon Chapel. Caroline, who has only recently come to join him from their native town of Hanover, is training to be a singer (she later took on a number of principal parts in William’s oratorio concerts), but they are neglecting their duties to make telescopes. The night sky holds as many wonders to them as the polyphonies of Handel’s music. In 1781, William Herschel discovered the planet Uranus and from then on, devoted himself only to making (even larger) telescopes with which he and Caroline could “sweep” the skies. Life had become one large and limitless adventure into the universe.

The Herschels felt, of course, that the universe could be understood in a language that we already possessed and that we could journey through it and catalogue it much as their acquaintances did of Pacific Islands and other terra incognita. We know now that we have no language with which to fully comprehend the universe, our ability to create new languages has been stretched to its limit by this challenge. Those High Priests who speak of unifying it all under M-theory cannot agree whether ‘M’ stands for membrane, matrix, mystery, magic or mother. They talk of super-symmetries and heterotic strings and insist that the universe has more dimensions than we can perceive which lie curled up somewhere within its fabric like some infinitely gentle, infinitely suffering thing.

We are generally agreed that the universe started with a Big Bang but what is its ultimate fate? Will it end in a Big Freeze, dissipating energy as it expands? Or is it a Big Crunch that we are facing where, once it has stretched itself too thin, the universe will contract again to the dimensionless singularity from which it came? Or will be the Big Rip where gravity finally fails us and all the stars and planets lose their integrity, and even atoms – just before the end – are torn apart? They are not nice-sounding expressions, the Big This and the Big That, they have a certain swagger about them which distracts from the enormity of each possible event. Much more pleasing in tone and texture is the idea of the Multiverse, where many ‘verses’ exist alongside each other and there is no ‘uni’ verse. Verses can collide and annihilate each other, but also spawn new verses, and set up in our minds a space that is more poetic and permanent.

Ultimately, it is all about the need to see what we cannot see, to know what we cannot possibly know, to give words to what cannot be spoken, to take what is immeasurably large and complex and fit it to the architecture of our perceptions and, in doing so, come a little closer to seeing into ourselves. Eugenia Balcell’s mesmerising installation captures this process by choreographing these glimpses into an endless and seemingly self-perpetuating cascade of collision and dispersion that continuously generates its own realities while still being constructed out of the stern stuff of the universe as we are able to observe and record it. She is performing what the Czech poet and immunologist Miroslav Holub did in the inverse, when he said of looking down a microscope:

Here too are the dreaming landscapes,

lunar, derelict.

Here too are the masses,

tillers of the soil.

And cells, fighters

who lay down their lives for a song.

Here too are cemeteries,

fame and snow.

And I hear the murmuring,

the revolt of immense estates.

Put an ear to the universe, and you will hear your own heartbeat.

Taken from Sunetra Gupta's Introduction to "Calcutta" by Benoit Lange

Now when I think of it - many years later and in a different land - my relationship with Calcutta during my formative years was not really one of engagement with the city itself, but with a particular strain of Bengali culture that had by then almost become divorced from the metropolis. We did not seek to ignore the city in the same manner as the nouveau riche ‘Anglicised’ community that we abhorred, who sealed themselves away from the growing squalor of the city in their airconditioned homes and chauffered automobiles, who consistently spoke English to each other instead of Bengali, wore denim dungarees and decorated their walls with posters of John Travolta and Olivia Newton-John. No, not us; we spoke and revered our mother tongue, used it successfully as a vehicle of every artistic activity, decorated our thoughts and memories with its abundant metaphors, revelled in the depth and breadth of our literary traditions which had shaped themselves so distinctly within as short a space as a hundred years. We rode the same overcrowded buses as those who went home to shanty town shacks without water or electricity or any sensible sanitation; we even held their children on our laps when there was nowhere for them to sit. But we never really knew the depths of their despair, the true horror of their condition, we allowed it to touch us briefly, like a dying moth that we would let fall casually from our limbs as we re-entered the security of our own lives. We performed our plays in the streets so that they could see, but the plays that we chose were Bengali translations of Bertolt Brecht and Jean Anouilh, and whether they really transcended the cultural boundaries that we sought to eliminate, we never really cared to know.

We did not try and alienate ourselves from poverty, and yet the true nature of poverty easily eluded us. In the seventies, conditions progressively deteriorated and we found that we could no longer afford eggs for every breakfast, found that we had to adapt to an average of eight hours a day without electricty due to power rationing in the seventies. All of this we bore with considerable fortitude, aided by our strong and unique sense of Bengali humour, only because the sideby sceptres of destitution and disease did not properly impact upon us. I did not know until many years later, after I started to study infectious diseases in England, that a million people were still dying of tuberculosis outside my door, for I had hardly heard of anyone getting the disease among our acquaintances. I did not know that by walking barefoot the young children were picking up hookworm that would eat away at their intestines with their sharp teeth, that the fumes from their mothers’ primitive stoves would congest their airways and make them prey to a thousand mortal respiratory infections. None of this, I knew then.

But it was not just the ultimate horror of true poverty that we quietly evaded in our seemingly uninsulated lives, we also chose to ignore – perhaps more consciously – the history of our city. There was a vague recognition that the year 1690 was the year of Calcutta’s birth, but precisely what this signified we did not know. We knew that it was the year in which an agent of the East India Company by the name of Job Charnock finally secured a site for a fortified factory on the east side of the river Ganges, where they could successfully defend it from the Mughal army, being bounded to the west by the deep dark river, and in other directions by salt marsh and jungle. It seemed ironic that our city – a city of poets as we saw it – should have been born out of such a confluence of commercial and military necessities – and in our minds, it became diminished as part of our real past. And because we could not accept Job Charnock as part of our cultural lineage, we spent very little time pondering the social circumstances of the time, how did they live these early settlers? what was the substance of their daily lives? Charnock, we knew, had saved a Hindu woman from her husband’s funeral pyre and lived with her in sin for many years. They had several children, and after she died, he built her a tomb, where he would sacrifice a cock on each anniversary of her death – a custom unheard of in Bengal. It was common at the time apparently for English Company servants to keep native women, to adopt native garments and eating habits. And where did these generations of half-caste children go, I wonder, for although there were one or two girls in my class with names like Sadie and Linda, the ‘Anglo-Indian’ community in the 1970’s in Calcutta was dwindling every day. Like so many of the visitors to the city over the years since its birth, they had come and gone, leaving only mysterious relics – like the Armenian Church or the Jewish Girl’s School, which we simply took for granted, treated them as labels, quite shorn of any history or meaning. One summer I took it into my head to volunteer at an Old People’s Home that I frequently passed on my way to the city centre – there I met an old Austrian woman who had been born and lived all her life in Calcutta. She had never visited Austria, and now would not know where to begin to search for any relations there. Her own brothers and sisters were all dead, and their children had left India long ago. She spoke of her life as a child in this city in a large family of Austrian immigrants with great fondness. She had never married, had stayed on, and now would spend what was left of her life within the confines of the rather gracious charitable institution that had accepted her as one of its residents. I held her withered hands and gratefully breathed the slightly rancid perfume of her nostalgia, but I was never able to see these lives as part of the tapestry of my past.

Another element of the city to which we were absurdly indifferent was the river, the great slow sore silted river which separated us from the main railway station of city – the Howrah Station. The Howrah Bridge, woefully inadequate for the volume of traffic that passed through it, had a certain majesty, but the hours that we waited upon it in traffic, anxious that we might miss our train, were only rarely spent in any sort of contemplation of the life that surrounded the river. Sometimes our gaze would perfunctorily drift towards the sections of stone step that punctuated the riverbank bearing such names as Prinsep’s Ghat (named after the extraordinary scholar James Prinsep, who deciphered many of our ancient scripts) and teeming with a life of a very different kind than that which we saw upon our doorsteps. The river was not integrated into our city, it did not define or comment upon it as did the Thames or more particularly the Seine. I never came to love it, nor to loath it either. It was just something that happened somewhere else, lovers went sometimes to walk on its banks, but we rarely made the journey, and when we did we were more concerned with the rows of junk food and ice-cream vendors than with the river itself, flowing sullenly by. But now I can see why it did not touch my life – Calcutta wore the river as an armour, it never chose to straddle and tame it. At one time it had afforded the servants of the East India Company “the diversion of fishing or fowling or both” (Hamilton, 1727), and the possibility of such excursions still remained, but it was never part of our daily existence. There is a new bridge now, a toll bridge no less, and when we visited last month an old schoolfriend took us for a ride in his smart new car across it and into the massive semi-urban sprawl beyond.

It is not a criticism that our love for the city was rooted neither in its history nor in its geography, for where it existed was in the life of the mind of its inhabitants. The landscapes of urban decay that we walked through every day provided a strangely neutral backdrop to our appreciation of poetry and music, and all our other spiritual quests. We invested heavily in emotions, in artistic and political opinions. We did not seek to sanctify either space or time by tracing its lineage but rather by its immediate associations. The grounds of the National Library were dear to us as where we held our most intense discourses, never did we stop to pause and wonder that it was in these gardens that Warren Hastings had fought his famous duel with Philip Francis, for what was now the National Library had once been his dear mansion, Belvedere. Our relationship with the city was essentially juvenile, unrooted, and charged therefore constantly with the indefatigable energy of youth. We were reluctant to assume permanent roles – actor one day, painter the next, and perhaps a physicist in the meantime as well. We defined ourselves only in the context of each other, institutions failed to label us, failed to oppress us. We moved with ease in and out of spaces still echoing the rigid order of the British Empire – our offices and classrooms - without ever being subdued by it. We travelled through streets where men and women toiled night and day, enslaved by their poverty, and we were not shaken. Sometimes we marched on the streets for them, but we knew that whatever economic eventualities engirdled them would never be able to hold us back.

I do not mean to say that we lived entirely on a metaphysical plane - there were certain elements of our reality that we very gladly embraced. The terrible beauty of the rains never failed to resonate within us, even though it meant that our homes would fill with bloodsucking insects, powercuts would become more frequent, tramlines would be flooded, and we would be forced to wade home from school through waist deep water that had just rinsed the pavements of all those bits of cowdung and betelspit we had picked our way through that very morning. Still, we waited and hoped for the rains, drank in the delicious perfume that rose from the famished earth as the first drops soaked into it with an excitement akin to lust. Indeed I believe my expectations of romantic love – in my youth, at least - were largely conditioned by my experience of monsoon, or perhaps more by its poetic treatment not only in the hands of Kalidasa and Tagore but also some of our lesser known writers. An important example for me is Buddhadev Basu’s extraordinary novel Tithidor where the heroine’s growing awareness of her sexuality is very specifically echoed by the dense voluptuous mystery of Shraban, the second – more mature – month of rain that follows Ashar, validated by the sense of secrecy and intoxication that hangs in the heavy air. It was in the month of Shraban that Tagore breathed his last, and every year on the 22nd day of Shraban, the dark skies would demand of us that we relive the grief of our nation in 1941, and the relentless rain would provide the ultimate accompaniment to our sombre memorial services. Life, death, and love – all seemed to be united by the rhythm of rain, and the perfect translocation of it into song. To this day, I do not know whether it was that Tagore had managed to capture and express the complex response of the Bengali psyche to rain or whether we – and I would be such a victim – had completely internalised what was actually his very personal response to the monsoon and made it our collective response. Whatever the case, they are his songs of rain that evoke for me most completely the essence of Bengal.

Lately, however, I have not felt so much the need to retreat into some private place, and listen for hours – usually in the dark – to these songs that so easily bring back to me the scents and sounds of rain, and so much more than that. The tapes that I relied upon for emotional sustenance ten years ago, lie gathering dust. It seems pointless to play them on a summer evening while watching the children frolic in the garden, nor do they beckon to me on a winter night even with the potential of brandy and firelight to create a more moody backdrop. Nor am I keen to listen to them on those many days when I am at my desk, and it is raining outside, has been raining for ever, for nothing is more dissonant with the music of this rain than the sad dripping English sky, they are like clashing shades of the same colour on the body of a person, I have to shut my eyes to force them apart again.

They are, nonetheless, the songs I sing to my children when they ask me to sing to them at bedtime. And sometimes I am briefly lost in the meshes of the emotions they recall, and they are bewildered, but soothed nonetheless.

Do you not know any English songs? the three year old asks.

Not many, I reply.

Why not?

Because I am not English.

I am pleased that this realisation should come to her in this way, through songs of rain that ache with unrequited love, rather than as a simple fact or just another part of the multicultural jigsaw that will be her life.

But the truth is that my relationship with these songs has changed, as has my dependence on memories of monsoon, so crucial to me at a time when my life was in a state of youthful convulsion, when they provided me with with a much-needed language for my pain. Someday again they may provide the same solace, but for now I am content with the sounds and smells of an English summer gathering pace outside my window, the peonies and the geraniums mingling graciously in the borders, the hornbeam hedge placing a barrier of calm between myself and the world.

What else do I retain from those emotionally vulnerable years spent at the mercy of the monsoon so long ago? For a long time it served as a surrogate for passion, which is useful thing for an adolescent, created within me a reverence for mystery, an early acknowledgment of the thin line between need and glut as one watched the parched earth easily turn to mud. But although it may have sensitised me to the misery of the nature, and to the misery of the many people suffered because of it – I cannot say that the rain taught me to be kind - for the atmosphere of the monsoon essentially encourages self-absorption, dignifies our petty experiences of pain as much as it provides us with a powerful means of expressing and coming to terms with our greater tragedies. For nothing brims as that first wet wind of the monsoon with the fullness of lust, nothing echoes the mystery of love quite as well as the dark lidded clouds, nowhere more is the pain of rejection better captured than in the wail of the relentless rain. How grateful I am to have been so immersed once, when I needed it most, in this magnicient metaphor.

The anxiety of expectation that surrounds the coming of the rains is hard to define. No season in England arrives in quite the same definite way – here, the transitions are either seamless or occur in a series of maddening flirtations – a few warm days to raise our hopes followed by weeks of frost. That was not how it was with the monsoon, for when the rains came, we knew that they were there to stay.

And although the winds were cooler for a while, the cynics among us knew this merely to be a prelude to an extended period of intense humid heat – the putrid months, as we called them, of August and September. And then, finally, would come the season that we call early autumn – Sarat – when suddenly we would wake to skies of incredible blue, a sweetness in the air that reached our nostrils even above the vehicle fumes. Graceful white kash flowers would spring up from unlikely corners, and as evening fell a healing amber light would touch the faces of the rain-ravaged buildings. This was a season that knew how to defeat the metropolis, whereas the rains did not, the rains had no clue, played straight into the hands of the monster that our beloved city had become.

The evenings would turn chilly, and our shawls and cardigans would have to be dragged out of their mothball laden trunks, grandmothers and aunts would get busy with their knitting needles to replace the ones we had outgrown or worn through. And gradually the air would lose its crisp newness as it absorbed the smoke of the thousands of coal fires that were lit in the streets to give some small heat to those without homes. Also the smoke from the solid fuel stoves could no longer rise very high in the cold heavy air, and would eventually gather as thick as a shroud over the city, through which the Christmas lights in Park Street would bravely shine. We were never quite sure whether it befit us to celebrate or even acknowledge Christmas, sometimes we would exchange small unassuming gifts. Our own main festivals of Durga Puja and Kali Puja occurred in the autumn, and were marked by several days of intense celebration in Bengal, but we did not know what to do about Christmas, felt uneasy about ignoring it altogether. Many of us had still been educated at some stage by nuns or priests or religious Presbyterians, and felt a certain loyalty to Jesus Christ as a person, if not as the son of God.

The game of cricket, always a running theme in our conversations, seemed to take on a new grace in the winter. The afternoons were speckled with the shouts of the boys playing in the streets, the dignified thud of the ball as it bounced off the bat and narrowly missed trickling into an open drain. My cousins and I would spend hours sitting by a radio the size of a modest cabinet in their living room, listening to the laconic commentators as they took us ball by ball through the five day international matches, so much of that air time must have been silence, even to think of it now is like drinking a glass of clear cold water. And afterwards, in the tropical winter stillness, we would read or quietly play chess, sometimes replacing our lost pieces with other objects like bottles of nail varnish or small tomatoes.

Mornings were more raucous, with the cries of hawkers selling everything from fresh vegetables to stainless steel cutlery, servants rushing to and fro on their various errands, the clash of pots and pans in the kitchen where lunch had to be prepared in time to be packed into steel tiffin-carriers and couriered by the ‘tiffin-wallah’ to the workplaces of the earning members of the family. Sometimes, just before lunchtime, the doorbell would ring and we would open it to find young women, fallen on hard times, trying to make a little money through door-to-door sales of new products. They would always be grateful to be able to sit down and for the glass of water that was offered them, would plunge into a description of the virtues of the creams and potions they were trying to sell, and sometimes would break down and plead with us to make a purchase. The plight of these middle class women touched us more than that of the labourers, paid by the hour, whom we could see carrying bricks to the building site across the road with their infants strapped to their sides. Breaches of dignity appeared to affect us more than basic human suffering.

Winter would give way to a brief Spring, and then the heat would start to build. We spent more and more time indoors, away from the ferocious sun. We wrote and acted plays, invented games that we could play with a pack of cards or on scraps of paper. We sprayed the hot floors with water to cool them and lay upon then under the trotting sounds of the ceiling fans, making up stories and silly songs. Solid sheets of obscene sunlight would invade through the slits in the shutters and from time to time we would hear the odd bark of a dog, or the snort of street cow. A few doors us was a metropolitan cattle shed which provided the neighbourhood with milk. This was in the seventies, now the streets are largely free of cows, although some buffalo still come to graze in the park outside my parents’ current home

In late afternoon, we would wash ourselves and douse our skin in talcum powder to keep away the heat rash, and then we would usually visit friends or relatives. Some lived in grand old houses with marble floors and heavy teak furniture, and others in cramped apartments sometimes near the very edge of the metropolis where a pleasant sense of rural peace encroached upon the urban squalor. Already their children had started to drift away to foreign lands, unlikely places such as Chile as well as the more usual destinations of Britain and the United States. My parents and I had lived abroad for the greater part of my early childhood, but it was always understood that we would return to Calcutta. And although I have lived in England now for over fifteen years, and perhaps will spend the rest of my life here, I cannot but see myself in this country as a visitor from Calcutta – a self imposed status with which I am thoroughly comfortable. Like Daniel Touchett in Henry James’s ‘The Portrait of a Lady’, I have found it ‘so soluble a problem to live in England assimilated yet unconverted’ that the readers who come to my novels looking for the anxiety of displacement often turn away disappointed. And why is it, I sometimes wonder, that I am rarely traditionally ‘homesick’, although of course - like anybody – I indulge in a degree of nostalgia regarding my past. Is it because, as I have discovered through writing this piece, that our relationship with Calcutta was never a deeply physical one? Or is it simply that the bonds between myself and the city are so deep that mere distance has no effect upon it? Perhaps it is because I have never tried to ‘belong’ in England that I retain, by default, a sense of belonging to Calcutta.

Whatever the case, there is no doubt that Calcutta prepared me most fully for a life elsewhere by attuning me so finely to the ironies of the human condition, and equipping me with the emotional and intellectual means to deal with them. It forced me into a dialogue early in life with my conscience: Was I betraying myself by purchasing a beautiful pair of sandals when children ran about unshod in the streets? Should I not donate to charity the money that I had saved on busfares, by walking to school all week, instead of using it to buy a bar of chocolate? And if I loved animals so, how was it that I could bring myself to eat them? And yet what right had I to refuse a piece of chicken when all around me children went for months without any protein? And so piece by piece, I acquired a moral framework which reconciled my privilege, unremarkable as it was, with the poverty that surrounded me. I realised I could be forgiven for not perceiving the true depth of a mother’s despair when she cannot feed her children, for such a nightmare is inconceivable until it actually happens to you. In negotiating a space to inhabit alongside poverty without being overwhelmed by it, we were forced to put human suffering in its context, and define the limits of our responsibilities.

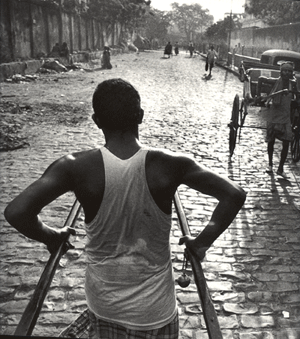

Perhaps it is the same when you look through a set of extraordinary photographs such as these, that in accepting their aesthetic you are forced to confront and perhaps redefine your own relationship with poverty and truth. The photographer has found beauty where I never chose to look for it, but this does not embarass me. Instead, I feel united with him in a quest to dignify and accept the lives of the people captured by his lens. One or two images resonate deeply with my own experience of the city – the painter at his easel, the violinist on the verandah, the fanlights, the tall shuttered windows, the broad balconies, the rain...

In the end, my strongest feeling about Calcutta is one of disappointment. Not because it has failed to clean up its streets, was wantonly torn down so many of the gracious buildings that once made it a ‘City of Palaces’, not because it has failed to give its citizens a better life. First of all, the streets are cleaner, people are less poverty stricken – and certainly more aware of their options – than in the days when I lived among them. As to its architectural heritage, there is a growing consciousness of its material, if not spiritual, value and browsing the internet I become aware that Prinsep Ghat, which I briefly mentioned earlier, has now been restored. “A new-look Prinsep Ghat” is the title of the article on www.bengalonthenet.com/attractions/misc . Bengalonthenet, eh? How things have changed! It is, in fact, an excellent little piece of writing, equally informative about James Prinsep and how for a long time this it served as a ceremonial landing and embarkation point for British dignitaries. More information on what to see and do in Calcutta can be found on various websites, such as www.kolkatabeckons.com/ which has also already adopted the new transliteration of its name – Kolkata. This latter development does not please me, I would prefer the lozenge-like quality of that particular sequence of syllables – ‘Kolkata’ – to be reserved for us, those of us to whom it conjures up much more than images of poverty, misery and decay. Hopefully no-one will be inclined to use it within an English sentence anymore than any self-respecting Frenchman would say: ‘I am going to ‘Pahree’ this weekend’. Paradoxically, this international validation of a ‘correct’ phonetic spelling of Kolkata signals to me a failure of the Bengali culture to truly sustain itself – which is where my real disappointment with the city lies, that it failed to nourish somehow what was an extraordinary vibrant and dignified culture, for what I grew up with as the culture of Calcutta has all but disappeared. By this I do not mean that the quality of the intellectual elite has declined – for very possibly it has not, although great poets, novelists and film directors we longer seem to have – but the spiritual concerns of the ordinary middle classes have very clearly shifted away from those that I had come to appreciate as a basic minimum among my fellow citizens. At the time, these were largely defined by the relatively recently deceased (1941) poet Rabindranath Tagore – so pervasive and absolute was his philosophy that when I was child I easily misconceived him as a divine being on account of ‘Tagore’ (or Thakur as it is properly pronounced – and here I have no qualms about this spelling being adopted internationally) translating as ‘Lord’. In my imagination, I saw the Lord Rabindranath perched upon a cloud, gently dropping sheets of poetry onto this earth. And yet later I came to see Calcutta as representing the dregs of this poet’s dream, came to feel that we had betrayed Tagore precisely by enslaving ourselves to his poetry. In fact, Tagore was an intensely practical man as well as a poet, considered the pursuit of earthly beauty as an essential process of the refinement of the spirit. Sometimes, sitting here in my garden in quiet contemplation of a perfect flower, I feel closer to his philosophy than amid the babble of a people ritually perfecting their imitation of his style in their prose, their poetry and their everyday speak. I cannot entirely ascribe the decay of the culture to the unhealthy dependence upon the vision, albeit grand and broad, of a single literary genius, but I am certain it had a major part to play.